The Third Dimension

Shaun Leonard, The Wild Trout Trust

Talk abstract: The Third Dimension. A plea to consider that third dimension of impacts to our rivers, that of physical damage. Quite rightly, there’s lots of media coverage and public outcry about pollution, then, at times of drought, lots of coverage of dry riverbeds, but we hear nothing about the physical damage we’ve been inflicting on rivers for hundreds of years and that continues today. It is this third dimension that, according to Govt data, is every bit as environmentally harmful as pollution or drought. In fact, few people know what a naturally functioning river should look (and sound) like, compared to an ecologically dysfunctional one. Let’s think why this matters, what are the causes and what’s being done to make the knackered less knackered. And, let’s join forces to tackle all three crises.

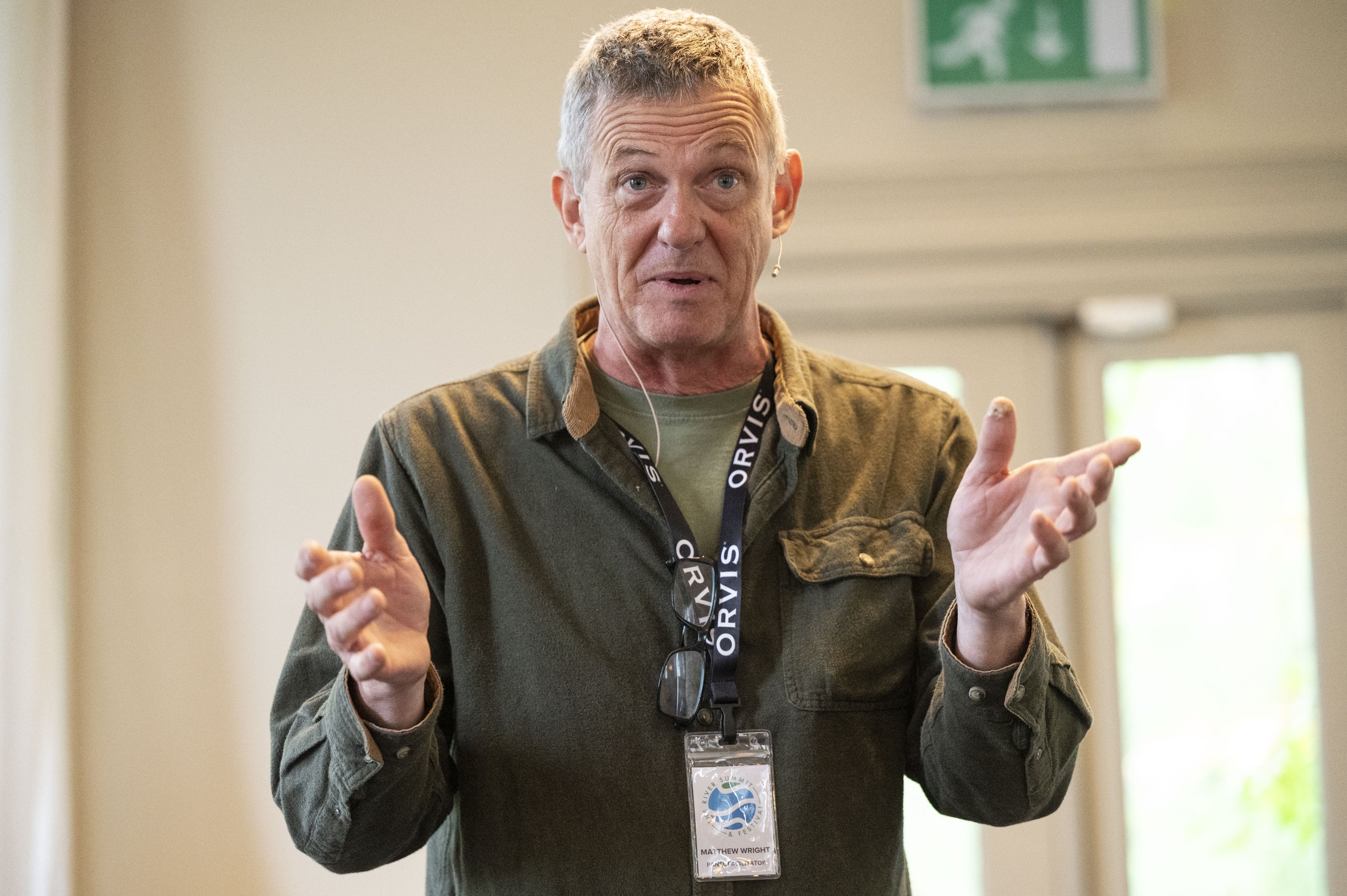

Shaun Leonard was our opening speaker at the UK River Summit, May 21st, at Morden Hall. Introduced by media personality and the ‘It’s not all about sewage’ panel moderator, Matthew Wright.

Read of Matthew’s close relationship with the River Wandle followed by a transcript of Shaun’s talk here:

“Morning everybody, I'm Matthew Wright. I'm moderating a couple of the panels today. I'm a South London boy, I grew up in Croydon. Had all kinds of interesting adventures in the Wandle Road car park. That was my first awareness of the River Wandle, but most of those I can't talk about here and you wouldn't want to hear. I've been fishing the River Wandle now for 10 years. Just twice a year, once at the beginning of the season and once at the end. Today is my first one of this year. I've been out already this morning at 8 o'clock and I've caught my personal best Wandle trout to boot, which is fantastic.

And every time I capture trout from the Wandle, I take a photo and send it to Theo Pike from the Wild Trout Trust, who was one of the guys pushing the role of the Wild Trout Trust in the River Wandle. And to see it grow gives me hope because a lot of what we're going to hear, I suspect, over the course of today is going to be a long way removed from hope. I think there's an awful lot to talk about. Sewage is clearly the predominant issue as far as the general public is concerned at the moment, which is why I think this first session, It's Not All About Sewage, should be really interesting because, as anyone who's really plugged into the water issue will know, it's not all about sewage.

Sewage is a big part, but it's not all about sewage.

And the first speaker is Shaun Leonard, Director at the World Trout Trust. Over to you, Sean….”

Shaun Leonard (a transcript): “Good morning all, my name is Sean Leonard. As Matthew introduced me, I work for an organization called the Wild Trout Trust. Our task in life is to do physical habitat improvement and that's largely what I'm going to talk about in the context of it being a third dimension. So the wildlife that lives in and by our rivers needs clean water, it needs enough of it, and this third dimension which is the physical structure that creates a habitat that supplies the needs of all the species that live in a river. River pollution is big news, as Matthew said, and I applaud and support the many people who are campaigning to stop slurry or sewage going into our rivers. You've heard lots about it in the media and you hear lots about it today. What's an even greater national disgrace is that this isn't new news. We've been polluting our rivers for hundreds of years. We created, we designed a combined sewer network that was designed to pollute and it's been doing it for 160 years.

What's changed is more people, more pressure on the system, a lack of investment in infrastructure that's gone on for four decades, a lack of policing on behalf of regulators and climate weirdness. So there's just increasing intense pressure all the time. And then in many years, and sadly more frequently because of climate weirdness, the headlines shift to dry rivers, dry river beds. And we see that scattered particularly across the chalk streams of South East England. And that's driven by climate weirdness but it's also driven by unsustainable abstraction.

And then there's this third dimension throughout all this, that of physical habitat, and it remains largely unrecognised. I'm going to tell you a bit about it now. Across the UK, physical damage to river habitat ranks about equal to pollution from sewage and farms as as the reasons for our river's poor state. In some places, let's go to South East Wales, Dylan (Roberts, GWCT) knows very well, the primary cause of issues for the rivers down there is farm pollution.

Elsewhere, like here on the Wandle, it's urban runoff and pressures of people, but it is also here a brilliant example of a river that's been physically damaged. Here it's got a long history, centuries history of damage from milling and then we basically turned quite a lot of the Wandle into an ornamental water feature, physical damage. Overall, over half of our rivers are regarded officially as highly or very highly damaged. This isn't new news either, we've been physically damaging our rivers for centuries. We've shoved them off to one side of the flood plain, we've straightened them, we've raised their banks to stop them sneaking out onto their flood plains, we've lined them in concrete, we've buried them underground, we've culverted them, and then when they start to misbehave, unsurprisingly, we dredge them. And in many places poor farming practice adds to that burden, tipping soil and nutrient on top of the problem. And societal consequences of that physical damage are manifest.

So we see rivers, perched rivers, that try get back to the bottom of the flood plain, they flood. We see straightened and straight jacketed rivers shooting water from A to B, where B just happens to be people's properties. When that dysfunctionality expresses itself, we all too often call in the men and machines scrape it and re-simplify the habitat. From an ecological point of view, the simplicity that physical damage creates just robs us of opportunities for wildlife. For example, a straightened river lacks variety of flow, depth and width that provides all those nooks plants and animals live in as their habitat.

When the river does try to mend itself, and they do given time, then again, we all too often, because it's deposited a bit of mud here, eroded a bank there, we very often just pull in the dredgers again to re-simplify the whole thing and restart the cycle. Many people love weirs. They have heritage, historical, archaeological significance. Ecologically they're monsters. We ecologists do not like them. River material, whether it's inert or living, needs to move. Fish need to migrate. Invertebrates disperse downstream. Gravel tumbles downstream, settling temporarily, creating habitat. What a weir does is it puts a brake on all of those natural processes.

Over time, material that's carried in the river, mud, sand, gravel, accumulates above the weir and progressively that accumulation becomes less and less home to fewer and fewer organisms. So, you end up with deep muddy deposits that are fantastic for sludge worms and midges, but very little else. How then I wonder should a natural river look? Well it's got trees on the bank providing partial shade, it's got a deep marginal fringe and that's a really critical bit because that's where the magic happens in a river. That connect between the river and the surrounding world which is at the edge of the river. It meanders, it erodes and it deposits stuff somewhere else.

So, it creates physical structure, physical variety, ecological variety. That's the gist of it. It connects along its length and it connects laterally to its flood plain. No weirs, no flood banks. What an ideal world. Many of our most famous rivers look nothing like this. I live in Hampshire between two of the most famous fished rivers in the world and quite a lot of those rivers look nothing like that at all. We've kind of set that in aspect because some of our most famous pieces of art show ecologically dysfunctional rivers, e.g. Constable's Flatford Mill. It might look pretty but it's an ecological nightmare. So what to do? Well, many people, like the Wild Trout Trust, like the Rivers Trust, are out there trying to undo the damage, re-naturalising bits of river, throwing in gravel, throwing in wood, taking down flood banks, taking down weirs.

And you could join that, you could join the Wild Trout Trust, you could join the Rivers Trust like Bell and South East Rivers Trust, you could join local Friends of groups, there are absolutely loads of them. And I guess the message is make habitat, don't destroy it. So leave stuff in the river rather than tidying, avoid tidying a river. And then my last plea I guess is for unity. So the groups within our world trying to improve rivers can be fractious. So I guess what I'm pleading for is for all of us to work together for more water, clean water and great habitat. Thank you. “